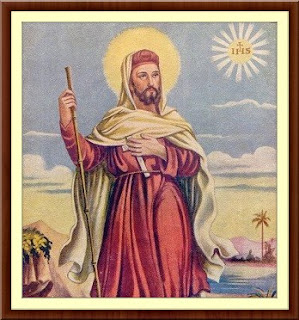

St. John de Brito, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary, emerges as a radiant beacon in the history of Indian Christianity, his life a testament to unwavering faith, cultural immersion, and ultimate sacrifice. Born in 1647 into the glittering courts of Lisbon, he abandoned privilege to pursue a perilous calling, arriving in Madurai, Tamil Nadu, in 1673 under the Tamil name Arul Anandar ("Blessed Grace"). Embracing the austere life of a sannyasi—an Indian ascetic—he bridged worlds, converting souls through humility and resilience, most famously a Maravar prince whose baptism sparked both a spiritual awakening and deadly opposition. This courageous act led to his brutal execution in Oriyur, Tamil Nadu, in 1693, cementing his legacy as a martyr. Beatified in 1853 and canonized in 1947, his feast on February 4 honors a life wholly given to the Gospel. This expanded account delves into his noble origins, his transformative journey to India, his innovative missionary work, the dramatic circumstances of his martyrdom, and the far-reaching legacy of a saint whose blood united continents in faith.

Early Life: From Royal Courts to Religious Zeal

John de Brito (João de Brito in Portuguese) entered the world on March 1, 1647, born into a distinguished noble family in Lisbon, Portugal, during the waning years of the House of Avis dynasty. His father, Salvador de Brito Pereira, a trusted diplomat and nobleman, served as governor of Rio de Janeiro under King John IV, while his mother, from the esteemed Almeida lineage, connected the family to Portugal’s aristocratic elite. As a child, John lived amid the splendor of the royal court, appointed a page and companion to the Infante Dom Pedro, the future King Peter II. This privileged environment offered him a life of ease, yet it also exposed him to the spiritual currents of the Counter-Reformation, a time when Portugal’s Catholic fervor was at its peak.

At age 11, in 1658, John’s life took a dramatic turn when he contracted a severe illness—possibly typhoid or smallpox—that brought him near death. His mother, in desperate prayer, vowed to dedicate him to God’s service if he survived, a promise rooted in the era’s deep Marian devotion. Miraculously recovered, John carried this vow as a sacred imprint. By his early teens, he encountered the stirring biographies of Jesuit saints, particularly St. Francis Xavier, whose missionary exploits in Asia captivated his imagination. These tales of sacrifice and adventure ignited a longing to forsake courtly life for a higher purpose.

In 1662, at the age of 15, John defied his family’s expectations of a noble career—perhaps in diplomacy or military service—and entered the Jesuit novitiate in Lisbon. His decision stunned his peers, given his frail constitution and the comforts he relinquished. His Jesuit formation was rigorous: years of philosophy at the University of Coimbra, theology in Lisbon, and hours of contemplative prayer honed his intellect and spirit. Despite recurring health challenges, his determination grew ironclad. Ordained a priest on February 3, 1673, at age 25, he wasted no time, petitioning his superiors for assignment to the Madurai Mission in India—a notoriously dangerous posting—driven by an ardent desire to follow in Xavier’s footsteps.

Journey to India: A Perilous Voyage and Cultural Immersion

On March 25, 1673, John embarked from Lisbon aboard a Portuguese carrack, part of a fleet bound for the East Indies. The six-month voyage around the Cape of Good Hope was a trial of endurance—tempests battered the ship, scurvy claimed lives, and cramped quarters tested his resolve. Arriving in Goa in September 1673, he stepped onto Indian soil at age 26, greeted by the humid air and vibrant chaos of Portugal’s colonial capital in Asia. Goa, with its grand cathedrals and bustling markets, was a gateway to the Jesuit missions, and John spent his initial months there acclimating and refining his skills under seasoned missionaries.

Assigned to the Madurai Mission in Tamil Nadu, he joined a legacy begun by Roberto de Nobili in 1606. Nobili had pioneered an inculturated approach, living as a Brahmin scholar to evangelize India’s upper castes, a method controversial yet effective. John embraced this vision wholeheartedly, traveling inland to Madurai—a city of ancient temples and intricate caste hierarchies, resistant to foreign influence. Under the tutelage of Jesuit mentors like Fr. António de Proença, he immersed himself in Tamil and Sanskrit, mastering the languages over two years to read sacred texts and converse fluently with locals. He adopted the name Arul Anandar, a Tamil honorific meaning "Blessed Grace," signaling his intent to blend into the cultural fabric.

Sent to the Maravar country—a rugged, arid region in southern Tamil Nadu dominated by the fierce Maravar warrior caste—John lived as a sannyasi. Clad in saffron robes, he walked barefoot across dusty paths, slept on mats under the stars, and ate sparingly—often just rice and lentils—mirroring the austerity of Hindu ascetics revered as holy men. This radical adaptation disarmed suspicion, earning him an audience among villagers and chieftains. His gentle demeanor, coupled with his command of Tamil poetry and proverbs, allowed him to present Christianity as a natural extension of their spiritual heritage, not a foreign creed.

Missionary Work: Evangelizing Tamil Nadu and the Maravar Prince

John’s ministry unfolded over nearly two decades (1673–1693), a period of relentless labor across Madurai, Trichinopoly (modern Tiruchirappalli), and the Maravar territories. He traversed jungles and rocky hills, establishing small churches—often simple thatched huts—and baptizing thousands, from fishermen to farmers. His approach was twofold: direct preaching to the masses and training local catechists—Tamil converts who sustained the faith in remote villages. Facing hostility from caste leaders and Brahmin priests, who saw his growing influence as a threat to their authority, he endured verbal attacks, threats, and occasional exile, yet persisted with quiet tenacity.

His ascetic lifestyle was his greatest witness. Sleeping on the ground, fasting for days, and rejecting European comforts, he embodied the sannyasi ideal, winning trust where words alone might fail. Jesuit letters reveal his impact: by 1680, he had baptized over 5,000, with communities sprouting in places like Manapparai and Siruvathur. He navigated India’s complex caste system with care, focusing on the lower and warrior castes while avoiding direct confrontation with Brahmin elites—a strategic balance learned from Nobili’s successes and failures.

The pinnacle of his mission came in 1690, when he converted Teriadeven, a prince of the Maravar caste in the kingdom of Siruvayal. Teriadeven, a polygamous noble with multiple wives, attended John’s preaching during a visit to a village chapel. Moved by the message of Christ’s love and the promise of eternal life, he sought baptism, a decision that required him to dismiss all but one wife—a bold rejection of Maravar polygamous tradition. John, aware of the cultural stakes, counseled him extensively, ensuring his commitment was genuine. The prince’s baptism, celebrated with a simple rite under a banyan tree, triggered a ripple effect: hundreds of his subjects followed, drawn by his example.

This triumph, however, sowed the seeds of John’s downfall. The dismissed wives, stripped of status, appealed to their families and local chieftains, accusing John of undermining Maravar honor and tradition. Their grievances reached Raghunatha Sethupathi, the Hindu king of Ramnad, a powerful ruler wary of Christian growth in his domain. The conversion of a prince—a symbol of his authority—crossed a line, igniting royal fury.

Martyrdom: The Sacrifice at Oriyur

In January 1693, John’s enemies struck. Acting on Sethupathi’s orders, Maravar soldiers arrested him near Siruvayal, chaining him in a mud-walled prison. For weeks, he endured torture—beatings with bamboo rods, exposure to scorching sun, and starvation—yet his spirit remained unbroken. Jesuit companions, like Fr. João de Faria, smuggled reports of his ordeal, noting his prayers for his captors and refusal to recant. On February 1, 1693, he was sentenced to death, a decree Sethupathi hoped would deter further conversions.

On February 4, 1693, John was marched to Oriyur, a village 50 kilometers from Madurai, chosen for its public square—a stage for his execution. Bound with ropes, his saffron robes tattered, he knelt before a jeering crowd of soldiers and onlookers. Raising his eyes to heaven, he prayed aloud in Tamil, forgiving his persecutors: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” An executioner, wielding a curved talwar sword, beheaded him with a single stroke, his head falling to the dust. His body was then impaled on a stake and left as a grim warning—a brutal end at age 45 that mirrored Christ’s Passion.

Far from silencing Christianity, his death galvanized it. Tamil converts hid his blood-soaked earth as relics, and within days, villagers whispered of his sanctity. Jesuit priests, risking their lives, retrieved his remains, burying them secretly in Oriyur. The site soon became a clandestine pilgrimage spot, its soil revered as hallowed ground.

Beatification and Canonization: A Saint Recognized

John de Brito’s martyrdom ripened into sainthood over centuries:

Beatification: On August 21, 1853, Pope Pius IX beatified him after a rigorous process confirmed miracles—healings and visions—attributed to his intercession. Tamil Catholics had long venerated him, and this recognition affirmed their devotion.

Canonization: On June 22, 1947, Pope Pius XII canonized him in a grand ceremony at St. Peter’s Basilica, a post-World War II moment celebrating missionary heroism. He joined a select group of Indian Jesuit martyrs, his sainthood a gift to a world recovering from conflict.

His feast day, February 4, marks his martyrdom, observed with Masses and processions in Tamil Nadu, Portugal, and Jesuit communities worldwide.

Legacy: The Red Martyr of Tamil Nadu

St. John de Brito’s legacy reverberates across time and borders:

- Veneration in India: In Oriyur, the Shrine of St. John de Brito, built in the 18th century and expanded over time, draws thousands annually, especially on February 4. Pilgrims honor him as “Arul Anandar” and the “Red Martyr,” a title evoking his bloodshed. Tamil Nadu’s Catholic community—over 6 million strong today—traces its resilience to pioneers like John, whose inculturated approach remains a model for evangelization.

- Jesuit Inspiration: His life galvanizes Jesuits globally, embodying their motto, Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam (For the Greater Glory of God). Retreats and schools bear his name, from Madurai to Lisbon, inspiring missionary vocations.

- Global Reach: Dubbed the “Portuguese Xavier,” he’s patron of missionaries and the Diocese of Sivagangai, his story a bridge between Portugal and India. His feast resonates in Portuguese-speaking nations, a reminder of their missionary heritage.

Relics—fragments of his robes, a lock of hair, and writings—survive in Jesuit archives in Rome and Madurai, venerated as sacred links to his sacrifice. Oriyur’s martyrdom site, now a serene complex with a church and Stations of the Cross, stands as a symbol of faith’s triumph over persecution, its annual festival a vibrant blend of Tamil and Catholic traditions.

Historical Verification

John’s life is meticulously documented:

Jesuit Letters: Over 50 letters, including his own and those of peers like Fr. Francis Laynez and Fr. João de Faria, detail his mission, trials, and death, preserved in Jesuit archives in Rome, Lisbon, and Madurai’s St. Mary’s College.

Local Records: Tamil Nadu’s oral traditions, passed down by Christian families, align with colonial accounts from Portuguese and Dutch traders, who noted his execution as a regional event.

Context: The Maravar caste’s martial culture and Ramnad’s resistance to Christian growth, documented in 17th-century chronicles like the Madura Manual, corroborate his story, as do studies by scholars like Fr. S. Rajamanickam and Dr. D. Ferroli.

A Life Poured Out in Love

St. John de Brito, born in 1647 in Lisbon’s royal courts, arrived in Madurai in 1673 as Arul Anandar, a Jesuit ascetic whose life of poverty and preaching transformed Tamil Nadu. Converting a Maravar prince in 1690, he faced martyrdom in Oriyur on February 4, 1693, beheaded at 45 for his faith. Beatified in 1853 and canonized in 1947, his feast on February 4 honors a sacrifice that echoes across centuries. From Portugal’s palaces to India’s villages, John’s journey embodied a radical love—embracing Tamil culture, defying death, and watering South India’s soil with his blood. His legacy endures in shrines, schools, and souls—a saint whose martyrdom radiates as a timeless beacon of grace.

.

%20Virgin%20and%20Martyr.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment